Earl Spencer and early boarding

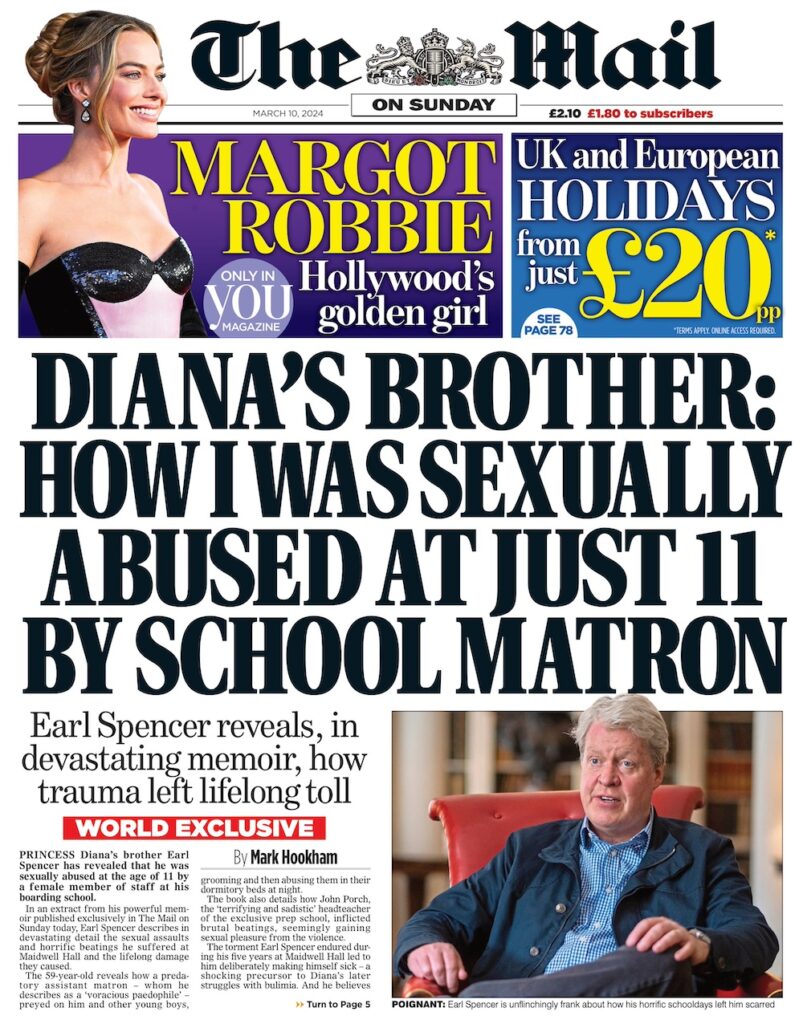

Last Sunday the Mail printed extracts from a new book by Earl (Charles) Spencer, the brother of the late Princess Diana, on his time at a private boarding school in England called Maidwell School (the school claims it has changed, but still offers two-weekly boarding for children as young as seven) which he attended between ages eight and 13; he experienced sexual abuse from a female staff member he described as a “voracious paedophile” while the then headmaster dished out “brutal beatings” and appeared to gain sexual pleasure from doing so. Early boarding — sending children to boarding school from primary age — has been a norm among the British aristocracy for generations and for many years this was inflicted on disabled children also, with schools for the blind, deaf etc taking in children from as young as four or five for their entire school lives; this practice has ended in this country, but it still goes on (albeit to a lesser degree than in the past) among the aristocracy. The practice of early boarding has received a greater degree of criticism than senior boarding, because it involves taking children from usually stable and functioning families and putting them in loveless institutions when they very much still need the love and attention of their parents. In the years since the Tories returned to power, the effect these places have on the men these boys become has been widely held up to scrutiny also.

I was in a boarding school from ages 12 to 16 and although I neither experienced nor witnessed serious sexual abuse, and none by any member of staff (although such things had happened earlier in the school’s history, resulting in some of the perpetrators doing prison time and one killing himself when police showed up), physical abuse was common as I have detailed here many times. What was more common than that was open and unchecked bullying; fifth-form prefects behaving like utter louts, punching and kicking boys in front of members of staff who did nothing, and in one incident I recall jumping on a first-year boy in the corridor and bellowing “keep your f***ing language down!”. The school boasted that it relied on “tried-and-tested old-fashioned methods” and that it was “structured and disciplined”, which I realised was a lie when I was made to live there; it was extremely chaotic and indisciplined, the only real ‘discipline’ was violence or the threat of it and mostly meted out to small boys. Certain members of staff were able to hold a civilised conversation with the more adult-like teenage boys (which there were more of, because few boys started at the start of secondary school but would mostly start in the middle of years 7, 8, or even 9, and because many were kept down a year, finishing year 11 at age 17 rather than 16) but were rude and dismissive when younger boys tried to engage them, especially if they made demands because of, say, bullying.

While I agree that early boarding must be condemned, we should consider “early boarding” to mean pre-pubescent boarding, not only primary-age (up to 11) boarding. When children enter secondary school at age 11, they do so very much as children. Boys, especially, are usually not even approaching puberty and are frequently smaller than most grown women. When they leave, they are adults in fact if not in name. By lumping these two groups together and expecting them to inhabit the same space, we endanger the actual children: they come to be seen as ‘youths’ whose misbehaviour is treated as more threatening than it actually is, and who require ‘discipline’ that would not be meted out to a child a year or so younger, but who are much easier to push around than someone in their mid teens who are, in the case of boys, sometimes as much as six feet tall; they thus become easy targets for the aggression of staff frustrated with dealing with older teenagers. Putting these two groups together is to give a group of adults free access to children but with none of the professional standards required of paid staff. This age range might have seemed like a good idea in the 1940s when compulsory secondary education was first introduced in the UK and the leaving age was 14, but it rose twice by the mid 1970s and the more of these unaccountable young adults you introduce, the more top-heavy the school’s population becomes and the more the staff’s time and skill set has to be oriented towards them.

In a boarding school, this age range is a recipe for disaster. Children have a right to their family, and parents have a duty to parent; no child should be separated from their family unless the family itself is the cause of harm. If a child is in a happy home and not being abused by anyone, why risk changing this by sending them to a boarding school which might, as soon as your back is turned, show your child a quite different face to the one it showed you? Add to this the fact that pre-teen boys are a favourite target for a certain type of paedophile, and the paedophile may not be the stereotypical guy in a dirty mac but the illustrious, cultured teacher who can write beautifully and play a dozen musical instruments whom any school that did not know better would consider a most valued member of staff and on past experience might turn a blind eye even if they suspected something was wrong. This was illegal in the 60s and 70s as well (as was using older boys as muscle to ‘discipline’ the younger ones); just because the beatings have had to stop because of changes in the law, do not think that abuse has stopped when school PR tells you they have changed. There is really no educational benefit and certainly no social cachet that can justify subjecting a child to any of this. Their place is at home, with their families, not in institutions, and it was about time this was recognised in law.