Has the “Human Rights movement” failed?

[How the Human Rights movement failed (from the New York Times)](https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/23/opinion/human-rights-movement-failed.html)

[How the Human Rights movement failed (from the New York Times)](https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/23/opinion/human-rights-movement-failed.html)

In this article, Yale law and history professor Samuel Moyn argues that the backsliding of various countries such as the Philippines and Hungary, whose leaders show explicit contempt for human rights and their defenders, shows that the movement for and idea of human rights is in crisis and the major watchdogs have failed to learn from the mistakes of the past:

> But from the biggest watchdogs to monitors at the United Nations, the human rights movement, like the rest of the global elite, seems to be drawing the wrong lessons from its difficulties.

>

> Advocates have doubled down on old strategies without reckoning that their attempts to name and shame can do more to stoke anger than to change behavior. Above all, they have ignored how the grievances of newly mobilized majorities have to be addressed if there is to be an opening for better treatment of vulnerable minorities.

Moyn argues that in the late 20th century when activists took up the cause of human rights when much of the world was under dictatorship, they forgot about “social citizenship”:

> The signature group of that era, Amnesty International, focused narrowly on imprisonment and torture; similarly, Human Rights Watch rejected advocating economic and social rights.

>

> […]

>

> In the 1990s, after the Cold War ended, both human rights and pro-market policies reached the apogee of their prestige. In Eastern Europe, human rights activists concentrated on ousting old elites and supporting basic liberal principles even as state assets were sold off to oligarchs and inequality exploded. In Latin America, the movement focused on putting former despots behind bars. But a neoliberal program that had arisen under the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet swept the continent along with democracy, while the human rights movement did not learn enough of a new interest in distributional fairness to keep inequality from spiking.

In other words, the narrow focus on campaigning against torture and the imprisonment of people for the mere expression of political or religious beliefs meant that the movement could not survive and maintain credibility when activists’ focus turns towards tackling the inequality and poverty caused by neoliberal politics which were favoured both by many of the dictatorships (especially in South America) and the democracies from which human rights campaigns were run: it begins to look like the two are in cahoots, allowing newly risen demagogues such as Duterte and Orban to be seen explicitly disregarding them.

I was never a member of Amnesty International, but I was briefly involved when I was at school (early 90s) as a relative, a friend and a teacher were members so I read various books, reports and magazines they produced and took part in some of their letter-writing campaigns. The focus on political prisoners was deliberate: the whole point was that we did not discriminate between different types of political regime or their approaches to economics. In the period from the 60s to the early 90s, much of the world outside Western Europe, North America and Australasia was under a dictatorship of some sort: one-party states in Africa and parts of south-east Asia, Communism in Eastern Europe and much of Asia, absolute monarchies in parts of the Middle East and fascist dictatorships in other parts, military dictatorships in South America and white minority rule in Southern Africa. Amnesty’s policy allowed us to put political differences aside to campaign against unjust imprisonment and torture in all of these places, with varying results; the fact that many of the regimes were western clients meant that we could (independently of Amnesty, of course) pressure our governments to stop supporting them or make foreign aid dependent on human rights pressure.

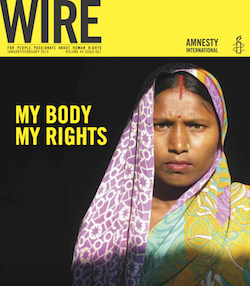

In my opinion, Amnesty has broadened its remit too much and in the wrong direction, towards campaigning for every pet cause of white liberals in its base countries — often things that not everyone can get behind. There were solid reasons for adopting a policy of opposition to the death penalty, because (particularly in the USA, the sole western country that still used it by the 1990s) it was frequently observed to be applied in a racist or capricious fashion or for political motives, but it still caused some discontent when people were asked to write letters in support of, say, a rapist and murderer facing the death penalty in Guatemala. The fact that it focussed on political prisoners, torture and the death penalty in the 1990s meant people of any religious belief could be involved and that schools, including Catholic schools, encouraged children to participate. *That was the whole point.* Now that it also advocates the legalisation of abortion and sex work, both of which attract large-scale religious opposition and the second of which is opposed by many non-religious people as harmful to women, the pool of potential participants is narrowed somewhat. Their campaign for wider reproductive rights (see [this magazine](https://issuu.com/amnestywire/docs/wire14_janfeb_web) whose cover is at the top of this entry), while not restricted to abortion, is far beyond anything we could have anticipated being asked to campaign for, or contribute to, until very recently; it was just not what Amnesty International was set up to campaign for. There never was any prohibition on people who were active members of Amnesty campaigning on these two issues, much as you could be a Thatcherite or a socialist in the 1980s and still participate, but many people will not want their membership fees going towards campaigning for the legalisation or decriminalisation of the sex trade.

It could be said that the Amnesty approach has become less fashionable because many westerners are more concerned about anti-imperialism than about the human rights records of some of the regimes abroad they consider to be “anti-imperialist”, often quite wrongly (Assad of Syria is not a western client but a client of the just as imperialist Russia and also Iran, which uses it to bolster its influence in the region). Association of the west with human rights undermines it when the west itself indulges in violent racism and blames the victims (the US in particular) and explicitly supports a racist ‘democratic’ regime in the Middle East, as well as its usual autocratic clients; the tendency of the west to close its mind, to turn in, often in ways that explicitly discriminate against minorities (e.g. Muslims) in their countries makes any talk of human rights look a lot like hypocrisy. All this enables dictatorships to use the “also defence” — to claim that their abuses are mirrored in the western countries whose activists (and celebrities) criticise them. Finally, the outward focus on human rights abuses everywhere but at home enables people to ignore abuses on their doorstep — physical abuse was rampant at the school I was at, ‘rights’ was a dirty word that was used contemptuously, and the teacher who introduced us to Amnesty was one of the abusers.

But that doesn’t mean the idea of human rights is a failure. Amnesty managed to operate in a variety of regimes for many years and its campaigns resulted in the freeing of many, many political prisoners; it indirectly mobilised support in rich countries for democratic reforms abroad and the maintenance of civil liberties at home when they were not always popular; the fact that, for example, it noted that trade and student unions were being targeted by dictatorships because they campaigned against impoverishment meant that these institutions gained sympathy. It did not have the answer to everything, but it has a lot of achievements it can be proud of and of those who have turned to fighting inequality now that the shackles of dictatorship have been thrown off, many are people Amnesty told us about in the 1980s or at least are associated with those people. It’s not *about* economic or social justice as such, but it helped those of us who fight for those things.