What’s missing from Bubb’s tepid report

This week the long-awaited report by Sir Stephen Bubb into the care of people with learning disabilities and autism following the scandal of Winterbourne View in 2011 was published. Titled “Winterbourne View: Time for Change”, it offers ten recommendations to the NHS, local authorities, the government and regulators including a “charter of rights” for people with learning disabilities, giving them and their families a right to challenge decisions and to request a personal budget, and a programme of closure for “inappropriate” inpatient care facilities, and has prompted a surge of media interest, the best being this piece in yesterday’s Guardian. Also this week, the inquest into the death of Stephanie Bincliffe from complications of obesity in an assessment and treatment unit, after seven years in a padded cell which she never left, was published, and although it criticises the institution she was in (run by the private Huntercombe group) for having no plan to treat her weight gain or challenging behaviour, it cleared them of neglect despite the egregious denial of her human rights and liberty over an extended period. (More: Mark Neary, Housing & Support Alliance.)

This week the long-awaited report by Sir Stephen Bubb into the care of people with learning disabilities and autism following the scandal of Winterbourne View in 2011 was published. Titled “Winterbourne View: Time for Change”, it offers ten recommendations to the NHS, local authorities, the government and regulators including a “charter of rights” for people with learning disabilities, giving them and their families a right to challenge decisions and to request a personal budget, and a programme of closure for “inappropriate” inpatient care facilities, and has prompted a surge of media interest, the best being this piece in yesterday’s Guardian. Also this week, the inquest into the death of Stephanie Bincliffe from complications of obesity in an assessment and treatment unit, after seven years in a padded cell which she never left, was published, and although it criticises the institution she was in (run by the private Huntercombe group) for having no plan to treat her weight gain or challenging behaviour, it cleared them of neglect despite the egregious denial of her human rights and liberty over an extended period. (More: Mark Neary, Housing & Support Alliance.)

This awful case shows how fortunate it was that there was one doctor (and it was only one of three who had that power) who saw that Claire Dyer did not need to be in a secure unit and could be at home, and released her from section only three months after her transfer from Swansea. If she had remained there, the situation could have got worse very quickly as the strain of living in an institution full of strange people and rules hundreds of miles from home and seeing family only once or twice weekly began to take its toll. This has happened to many others, as the families of Stephen Andrade (held in St Andrew’s in Northampton; home is London) and Tianze Ni (held in a hospital in Middlesbrough; home is Scotland) have testified. The BBC had interviews with Stephanie’s mother and sister, and the mother said that Stephanie was extremely distressed by her situation; she believed she had been kidnapped and told her she had been ‘trapped’ and wanted to come home. She saw the staff as “the people who were holding her” which is why she attacked them when they came and went without letting her out. This casts doubt on the claims that they allowed to put on ten stone and left her in that wretched condition until she died just because any attempt to address her dietary issues would have triggered self-injurious behaviour. Frankly, the excuses don’t wash and I wonder how well-informed the coroner was to accept their opinions. If they could not care for Stephanie properly, they should have found whoever could, and wherever.

The Bubb report has been widely panned by the learning disability advocacy community. That community are trying to get a legal framework for making sure people with learning disabilities or autism do not end up in units unnecessarily, or sent a long way from home, or have their human rights infringed in other ways. That effort is known as the “LB Bill”. If you do a simple page search of Bubb’s report, you will notice that the letters LB appear only in the word “wellbeing” (three times) and “bill” only appears as part of the word “billion” (once). A key section of the proposed bill is to exclude autism from the Mental Health Act except when there are co-morbid mental health illnesses; no such provision appears in Bubb’s report. The problem with the MHA in regard to autism is fairly simple: it gives too much power to psychiatrists who are not often autism specialists (indeed, this fact is often used as an excuse to transfer patients, not necessarily to places where there are any autism specialists). It takes only two of them to section someone, and the process for getting someone off a section without their say-so is long and complicated, and the lapse and renewal of a section puts the process back to square one. It allows them to treat challenging behaviour with psychiatric medication, which causes weight gain, can lead to liver damage, and does not address the causes of their behaviour but only the symptom itself. The report does not suggest that there should be a discipline of autism specialist, which can replace the role of psychiatrist or at least greatly reduce it.

A key recommendation is that personal budgets be made available to the people who are at risk of being admitted to a unit, or are already in one. This seems to be a response to the continual complaints that bad institutional care is expensive — thousands or tens of thousands per week — but the report does not address the problems with personal budgets, such as that the person running it, if they choose to employ staff directly rather than using agencies, becomes an employer and is reponsible for paying their staff’s income tax and National Insurance, and that many local authorities make life difficult for people using them because they are convinced people are out to defraud the system, as Mark Neary has exposed in a number of blog posts since he started using one to pay for his son Steven’s care. It is time-consuming and a huge responsibility with a lot of legal pitfalls.

Another thing missing from the report is any proposal to improve the standards required of institutional care workers other than nurses, in terms of training or qualifications, as besides being abusive towards patients, the staff responsible for the original Winterbourne View scandal were clearly not of the necessary calibre and I suspect this could have been gauged in some cases with one face-to-face interview. While it’s true that a qualification does not make someone a good carer, anyone applying for a caring role should be able to present either a qualification or some evidence that they can care, have been a carer, or have an understanding of learning disability, autism or the responsibilities of the job. If their pay were increased, it might be possible to expect better standards of them.

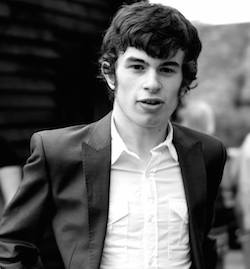

Also missing from the report is any mention of making sure mental health services, for learning disabled people or anyone else, look after patients’ physical health as well. This was a major factor in the death of Connor Sparrowhawk (left): staff did not consider that a man with a learning disability also had a chronic physical condition (epilepsy) which could be life-threatening, despite having been notified of it by his family and despite it being common among people with learning disabilities. The CQC report also noted that medicines at that unit were not kept refrigerated and there was no battery in the defibrillator. A less serious incident of such neglect was the woman admitted to a secure unit who was not provided with the incontinence pads she needed, presumably because the unit, which did not cater for learning disabilities, rarely needed to deal with that problem (although I find that difficult to believe). This type of neglect is not restricted to ATUs or learning disability mental health care: only last night a woman who was admitted last week to a psychiatric ward miles from home (because the women’s ward at her local unit, the Orchard in Lancaster, has been reassigned for male use) had an asthma attack and was without her inhaler. It took two hours for staff to take her to the urgent care centre and although the care there was excellent, it could have been avoided if the ward could have provided an inhaler, or she had been in the local unit and able to access hers from home which was only 15 minutes away. Surely any hospital, and certainly any hospital ward which confines people, which nearly all psychiatric wards (including ATUs and including those that hold informal, i.e. non-sectioned, patients) do, should have the facilities to deal with an asthma attack as a severe one can kill in much less than 15 minutes.

Also missing from the report is any mention of making sure mental health services, for learning disabled people or anyone else, look after patients’ physical health as well. This was a major factor in the death of Connor Sparrowhawk (left): staff did not consider that a man with a learning disability also had a chronic physical condition (epilepsy) which could be life-threatening, despite having been notified of it by his family and despite it being common among people with learning disabilities. The CQC report also noted that medicines at that unit were not kept refrigerated and there was no battery in the defibrillator. A less serious incident of such neglect was the woman admitted to a secure unit who was not provided with the incontinence pads she needed, presumably because the unit, which did not cater for learning disabilities, rarely needed to deal with that problem (although I find that difficult to believe). This type of neglect is not restricted to ATUs or learning disability mental health care: only last night a woman who was admitted last week to a psychiatric ward miles from home (because the women’s ward at her local unit, the Orchard in Lancaster, has been reassigned for male use) had an asthma attack and was without her inhaler. It took two hours for staff to take her to the urgent care centre and although the care there was excellent, it could have been avoided if the ward could have provided an inhaler, or she had been in the local unit and able to access hers from home which was only 15 minutes away. Surely any hospital, and certainly any hospital ward which confines people, which nearly all psychiatric wards (including ATUs and including those that hold informal, i.e. non-sectioned, patients) do, should have the facilities to deal with an asthma attack as a severe one can kill in much less than 15 minutes.

Bloggers Steve Broach and Chris Hatton have also drawn attention to its lukewarm attitude towards the rights of people with learning disabilities: it proposes a “charter of rights” but this does not include new rights but merely re-emphasises existing ones, nor does it propose any means of enforcing them, such as legal aid which is being cut. The report proposes a “right to challenge” decisions, but these rights already exist such as the right to judicial review, but as the Dyers found out in July, it is difficult to make a case to challenge a clinical decision even when it is plainly against the patient’s best interests. Section 2.2 says “the review triggered by this right to challenge would only recommend admission/continued placement in hospital if it concluded that the assessment, treatment or safeguarding could only be effectively and safely carried out in an inpatient setting”; however, it may be that a judge is easily persuaded that this is the case or indeed biased towards accepting clinicians’ or social workers’ opinion. The right to challenge does not equate to the right to overturn an unwanted decision that is not in one’s interests.

The media coverage of this report continually cut to footage from Winterbourne View in 2011 with the words “viewers may find some of these scenes disturbing” or words to that effect. The thing is that not every kind of abuse of the human rights of disabled people would necessarily make shocking footage, much as torture would, but long-term imprisonment of a political prisoner would not, but is still a major violation of their human rights. Neglect, lack of control and long-term misery do not make headlines or shocking images, but that is the best some NHS trusts and private care companies can offer Britain’s learning disabled people and the opportunities for challenging them are limited. They have a right to control over their lives, to personal freedom, to family life and to freedom from abuse, and when they need to be cared for, they have a right to be cared for well. This report does not really investigate why these are not happening for many people, is not really based on listening to those affected and those who love and care for them, and will not lead to well-entrenched rights and robust mechanisms to resist bad decisions. It’s great that the report, and perhaps Stephanie Bincliffe’s inquest, has brought individual cases of bad care and long-distance placements into the public eye for a day or so, but the people affected need to be listened to. They are all behind the LB Bill. Let’s not settle for this tepid report.

The media coverage of this report continually cut to footage from Winterbourne View in 2011 with the words “viewers may find some of these scenes disturbing” or words to that effect. The thing is that not every kind of abuse of the human rights of disabled people would necessarily make shocking footage, much as torture would, but long-term imprisonment of a political prisoner would not, but is still a major violation of their human rights. Neglect, lack of control and long-term misery do not make headlines or shocking images, but that is the best some NHS trusts and private care companies can offer Britain’s learning disabled people and the opportunities for challenging them are limited. They have a right to control over their lives, to personal freedom, to family life and to freedom from abuse, and when they need to be cared for, they have a right to be cared for well. This report does not really investigate why these are not happening for many people, is not really based on listening to those affected and those who love and care for them, and will not lead to well-entrenched rights and robust mechanisms to resist bad decisions. It’s great that the report, and perhaps Stephanie Bincliffe’s inquest, has brought individual cases of bad care and long-distance placements into the public eye for a day or so, but the people affected need to be listened to. They are all behind the LB Bill. Let’s not settle for this tepid report.

Possibly Related Posts:

- Travesty of justice, travesty of science

- Autism, female diagnosis and trauma

- “Have you tried boarding?”

- How we still let our learning disabled down

- Burning your child’s past